Baleo! Baleo! — “The hunt is on!” The cry resounded through the village. A minute before, a motorboat had raced into the bay, and its crew had screamed the signal to the men on the beach, who themselves had taken up the cry. Now every man, woman, and child who had heard their alarm was adding a voice to the shouted relay, until all fifteen hundred souls in the ramshackle houses and surrounding jungle chorused that the sperm whales had been sighted.

When the clamor reached Yohanes “Jon” Demon Hariona in the decaying home he shared with his grandparents and sisters on the cliffs above Lamalera, he grabbed a baseball cap with frayed threads tasseling its brim, a battered plastic water jug, and a pill bottle stuffed with tobacco confetti and dried palm- leaf rolling papers. Then he dashed down steps chiseled into the stone of this Indonesian island, pushing aside hallooing children as he went.

On the beach, Jon’s tribesmen were already shoving the téna, their wooden whaling ships, across the sand and into the surf. Captains yelled exhortations at their crews. Jon set his shoulder against a thwart of Boli Sapang, the téna belonging to his clan, the Harionas, and strained with a dozen other men to launch it. Once the water unyoked the weight of the boat from him, he leapt aboard.

In the past, he had always manned one of the eight slim common paddles in the center of the téna, but he saw the left befaje oar, with its huge circular face, lying unclaimed at the prow, and raced to seize it before anyone else could. Recently engaged to be married, he fancied that he had matured beyond his twenty- two years. As the crew rowed through the breakers, he pulled the befaje oar, showing off his strength to his elders. But he had another reason for claiming the great oar: it was located directly behind the harpooner’s platform, so the two befaje oarsmen were sometimes called upon to aid the harpooner. Jon had wanted to be a lamafa, a harpooner, all his life. There was no higher honor for a Lamaleran man.

For nearly three hours, the fourteen téna of the Lamaleran fleet chased the spouts of three young bull sperm whales across the Savu Sea, repeatedly closing in only to be saluted by the animals’ flukes as they dove. Finally, Ondu Blikololong, the lamafa of Jon’s téna, screamed, Nuro menaluf! — “Hunger spoon!” or, colloquially, “Row as fast as you’d spoon rice if you were starving!” Or perhaps most accurately, “Row like you want to feed your families!”

Ten hand-carved paddles ripped the sea in professional unison. The thirty-foot sperm whale breached ahead of them, seawater cascading from its flanks. Although the leviathan measured only about the same length as the téna, the beast outweighed their vessel by at least twenty tons.

“Row like you want to feed your families!” Ondu shouted hoarsely, balanced at the front of the téna.

A nasal boom echoed as the whale exhaled. Then droplets showered the hunters: mucous and warm, distinct from the chillier spray off the ocean, as if the whale had blown its nose in their faces. Everyone on the téna knew the animal was filling its colossal lungs for a dive that could last half an hour. Time was short.

Ondu had been holding his sixteen- foot- long bamboo harpoon horizontally like a tightrope walker to balance himself against the unpredictable pitch, roll, and yaw of the téna, but now he turned the weapon vertical, and aimed the spearhead directly down. “Row like you want to feed your families!” he yelled once again.

Jon braced his feet against the hull and pulled his oar until a headache simmered in his skull and his chest ached. Because the befaje oar faced the stern, while the other paddlers faced forward, he had to keep glancing over his shoulder to track the whale.

Ondu crouched at the tip of the hâmmâlollo, the bamboo platform jutting five feet from the prow. His triceps quivered with the effort to poise the harpoon above his head. The platform edged forward, closer and closer, until his shadow dulled the sunlight glittering on the whale’s sea-glossed back, until the prow almost nudged the fleeing animal, until it seemed that he would never jump. Then he dove off the hâmmâlollo with kamikaze grace, both hands choking the bamboo shaft, and rammed the weapon into his prey with his entire bodyweight. The harpoon shaft shuddered, bent, and then straightened — but Ondu kept going, rebounding off the flank of the whale and into the sea, his arms and legs flailing. The bamboo remained planted in the animal, quivering.

The sperm whale thunderclapped the ocean with its flukes. A wave swamped the bow of Boli Sapang. The harpoon rope zipped so fast across the railing that it smoked, and an oarsman doused it with seawater to prevent it from igniting. The line was tied from the head of the harpoon to the aft of the téna. When it ran out, it jolted the entire ship, almost hurling Jon off his oar. The hawser thinned, with water spitting from its elongating threads, and hummed as it vibrated. The téna lurched forward, plowing through the waves as the whale dragged it like a horse drawing a sleigh.

Jon rushed to stow his oar and help the second harpooner, Fransiskus Boko Hariona, a distant uncle, set the two safety ropes that would prevent the harpoon line from running wild. In the depths, the sperm whale reversed direction, yanking the line against the left safety rope and bending it inward until it creaked. The crew shouted as the boat spun. The whale was striving to get lower, into a deep current that could carry it to freedom.

Then Boko hollered and snatched at two lengths of rope writhing like stepped-on snakes — the left safety rope, three fingers thick, had snapped in two. Boko raced to tie together these broken halves to corral the rogue harpoon line.

In the confusion, the right safety rope had also come undone. Jon stepped over the harpoon line and reached for it. A sudden crushing pain clamped onto his right calf. The harpoon line had broken through Boko’s makeshift knot and swung against the left side of the boat, pinning Jon’s leg against the hull so that he was bent over the railing, as if vomiting into the sea. He twisted, trying to get a better grip on the rope, but it was as unyielding as an iron bar, drawn taut by the thirty tons straining at the other end.

Jon remained silent as the line sawed across the back of his calf, tearing off skin. He hoped he could extricate himself from this predicament before his elders noticed. Misery elongated the seconds. He lost track of time. He had never considered the old men who hobbled through the village on stump legs with anything more than a teenager’s derision, but suddenly he saw that he might join their ranks. A flensing knife lay within reach. He could cut the rope and save his leg. But if the whale escaped, his clan might lack meat for months and his elders would accuse him of valuing his own life over the well- being of the tribe. No, he would have to hope the whale snapped the rope.

Boli Sapang was shaking now. The left railing tipped toward the sea. Though the ocean was calm, the ship rocked as if beset by five- foot waves, more heavily to the left with each heave. The crew mobbed to the right side of the téna to counterbalance it, but they were lofted like eleven men on the losing end of a seesaw. Only Jon remained on the left side, looking up helplessly at his clansmen. When the téna was almost vertical, the crew leapt into the water. Jon alone remained aboard, clawing at the rope, screaming. The boat capsized.

Darkness. A maelstrom of bubbles. Harpoons, ropes, knives, palmleaf cigarettes, sharpening stones, bamboo hats, ratty T-shirts, and flipflops — detritus of every kind sank with Jon. Above, silhouetted men kicked through flotsam and away from the overturned téna, which was being dragged beneath the surface. No matter how hard Jon stroked toward the sunlight, he still descended. Pain pulsed in his leg such that his ankle felt as if it were being twisted off. He glanced down through the murk: wound like an ampersand around his foot, tethering him to the whale diving into the abyss, was the harpoon rope. He yanked at it, but it was a rigid line, without so much as a wiggle.

At first, he feared nothing, certain that he had no sins on his heart and so his deliverance was guaranteed by the Ancestors, the spirits of past whalers whom the tribe worshipped. But he soon remembered that his Hariona clansmen had trespassed against the Ancestors and that the spirits required a sacrifice to forgive the wrong. He could feel the ghosts, risen from their seabed graves, thronging around him. He prayed to them and to Jesus that the rope would loosen, that the whale would surface.

He was an orphan, after all, and it was his responsibility to provide for his infirm grandparents and younger sisters, and soon for his fiancée. Who would bring home the whale meat if he did not? Bubbles wobbled above him. Air — his air, he realized, escaping his lungs.

Only by somehow outpacing the whale would he be able to put enough slack in the line to untangle his foot. As his brain fizzed for lack of oxygen, he inverted himself and swam into the depths.

About five centuries ago, on the western rim of the Pacific Ocean, a tsunami obliterated the village of a band of hunter- gatherers now known as the Lamalerans. After a harrowing odyssey, the survivors built a new home on Lembata, a backwater island so remote that today other Indonesians call that corner of their nation “The Land Left Behind.” The shore of Lamalera Bay is too rocky and parched to grow crops, but the newcomers soon discovered that even one of the sperm whales schooling just offshore would provide enough meat to feed everyone for weeks. To survive this harsh environment and the dangerous work, the Lamalerans evolved a unique culture that has been rated by anthropologists as one of the world’s most cooperative and generous, a necessity when it comes to coordinating dozens of men to defeat colossal whales and then equitably share the bounty.

Today, the Lamalerans are among the small and ever-dwindling number of hunter-gatherer societies remaining in existence, and the only one to survive by whaling. Although the Lamalerans will harpoon anything from porpoises to orcas, their main prey are sperm whales, the largest carnivore in history. The tribe’s three hundred hunters take an average of twenty a year, enough to sustain all fifteen hundred of their people with the jerkied meat through the lean monsoon season, when storms make it difficult to launch their ships. While several Inuit communities also still whale, those arctic seafarers increasingly derive their sustenance from imported packaged food and mechanized fishing methods, making the Lamalerans the world’s last true subsistence whalers. Indonesia is not a signatory to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, but even if it were, the agreement still permits aboriginal subsistence hunts like the Lamalerans’. Moreover, the sperm whale is not endangered, with several hundred thousand surviving in the wild, meaning the tribe has little impact on the animal’s global population.

For hundreds of years, the hunt has been the foundation of the Lamalerans’ nutrition and culture. Even as neighboring tribes have abandoned ancient occupations for modern ones, the Lamalerans have preserved their unique livelihood by limiting foreign influences, worshipping their forebears, and defending the Ways of the Ancestors, a set of whaling and religious practices handed down through the generations. Though outside ideas—Catholicism spread by Jesuit missionaries, for example—have taken root in the tribe, the ancient beliefs remain strong, and the whalers continue to practice shamanism.

But over the last two decades, the Lamalerans, like many other indigenous peoples, have been ever more pressured by the free flow of information, goods, and technology that has transformed even the remotest corners of the earth. Today, the tribe is threatened by its youth abandoning whaling to seek a modern life, by industrial trawlers overfishing its waters, by businessmen and foreign activists attempting to change its livelihood, and by internal battles over how to cope with the conundrums posed by modernity. Unless the Lamalerans can figure out how to navigate these proliferating troubles while remaining true to their identities, they confront their end.

They are not alone in this struggle. Since Europeans began colonizing other continents in the sixteenth century, an accelerating wave of cultural extinction has halved the number of cultures worldwide, with thousands lost in the last century alone and thousands more predicted to be obliterated in the next few decades. In 2009, the United Nations reported that many of humanity’s 370 million indigenous people were enduring threats similar to those the Lamalerans face, for though the Lamalerans are almost unique as whalers, numerous groups still survive as herders, swidden agriculturalists, and hunter- gatherers.

The Lamalerans’ experience, then, speaks not just to the danger faced by earth’s remaining indigenous peoples but to the greater cultural extinction humanity is suffering. Before agriculture was invented, every human was a forager. In the transformation from our first identity to our modern one is the story of how our very nature has changed — for better and for worse. As the number of ways to be human rapidly diminishes, all people, whether in industrialized or traditional societies, must ask: What is being lost as our original modes of life die out? Who are we now? And who will we become?

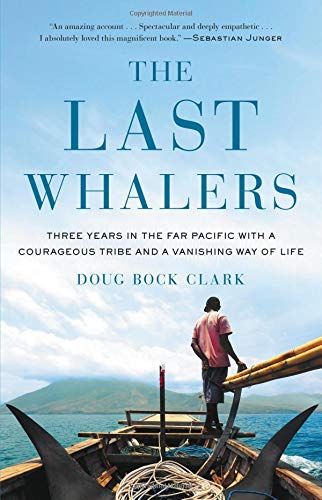

Doug Bock Clark is a Visiting Scholar at NYU's journalism institute whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, GQ, WIRED, The New Republic, Men's Journal, The Atavist, and the website of The New Yorker. He’s on Twitter handle as @DougBockClark. The Last Whalers (Little, Brown), his first book, can be purchased on Amazon now.

Doug Bock Clark is a Visiting Scholar at NYU's journalism institute whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, GQ, WIRED, The New Republic, Men's Journal, The Atavist, and the website of The New Yorker. He’s on Twitter handle as @DougBockClark. The Last Whalers (Little, Brown), his first book, can be purchased here.